Introduction

Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) can resolve abnormalities within the coronary artery to a degree that is not possible with angiography alone. With an axial resolution of 70-200 μm and lateral resolution of 200-400 μm, IVUS can provide information on arterial wall and luminal composition that can change clinical management decisions.

This document describes scenarios of clinical uncertainty where the coronary angiogram has not provided enough information. It also gives examples of how IVUS can help to clarify decision-making in such cases.

Scenario 1. Overlapped vessels on angiography

No matter how skilled the radiographer, sometimes the vessels of the left system can be overlapped on angiography such that it is difficult to be certain whether the luminal character is normal. An extreme example of this phenomenon is given below to illustrate how IVUS can allow treatment in patients where vessel overlap limits views of the coronary arteries.

A 78-year-old male with end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease developed chest pain while he was an inpatient on the respiratory ward. He was receiving antibiotics, nebulisers and steroids. Marked bronchospasm was apparent and he had previously been declared at high-risk for intubation and ventilation, given the severity of his lung disease.

The patient’s electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed anterior ST elevation. On examination, he looked pale, sweaty and was in distress. He consented to primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and, in discussion with the intensive care team, agreed he would not be intubated for the procedure. He was unable to lie flat and so was propped up at a 60-degree angle, limiting the range of movement of the image intensifier.

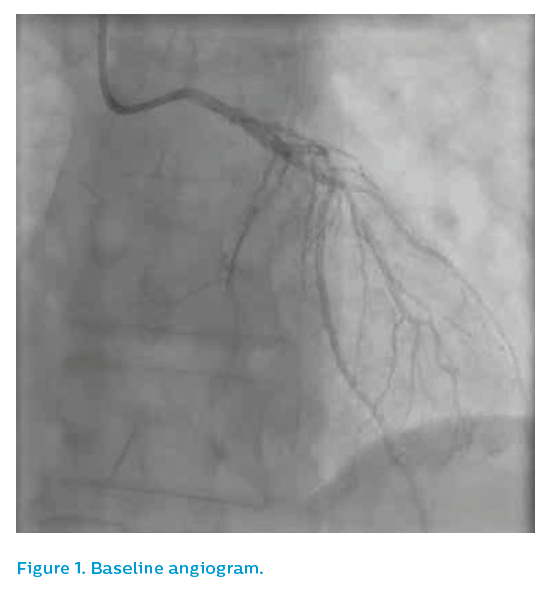

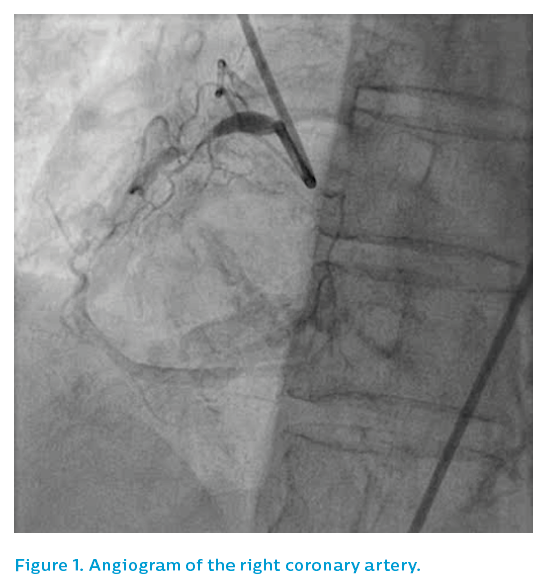

Angiography from a modified posteroanterior caudal view produced an image of overlapped vessels, see Figure 1. The guiding catheter engagement damped the haemodynamic trace, further degrading the image quality, see Figure 2. It was elected to IVUS the left anterior descending artery, which now appeared to have flow despite the persistence of ST elevation on the ECG.

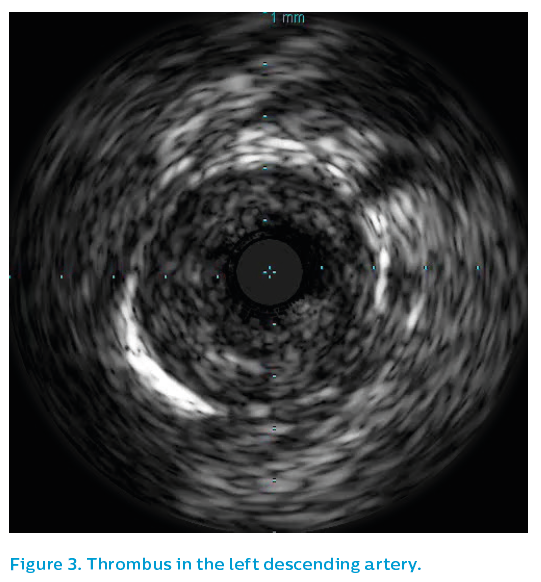

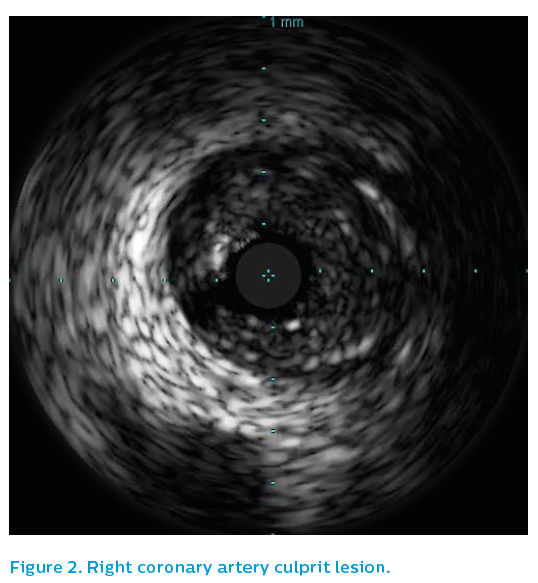

Initial IVUS showed a critical lesion in the proximal left anterior descending artery with thrombus present, see Figure 3. Using the SyncVision® Precision Guidance system, the lengths and positions of the stents required could be planned. Angulation at the origin of the left main artery made catheter engagement difficult throughout the case, leading to poor angiographic quality.

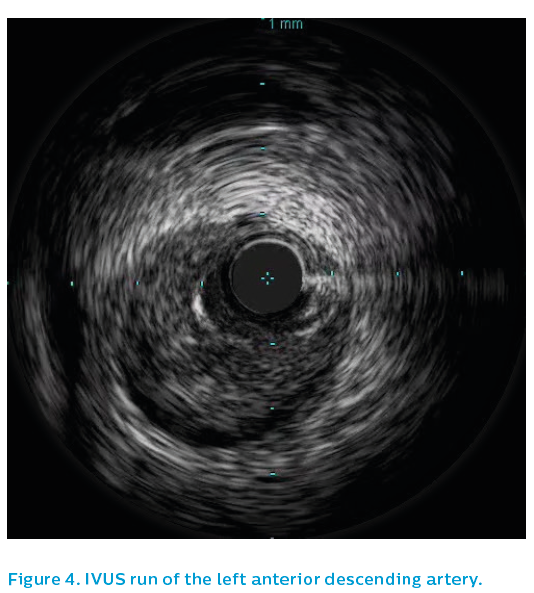

The final IVUS run demonstrated underexpansion in the mid-section within a positively-remodelled section, see Figure 4. This was subsequently addressed with a 4 mm non-compliant balloon, leaving a nice stent result. The left main artery demonstrated only mild, non-obstructed eccentric plaque. As can be seen in Figure 5, without IVUS the final image quality using angiography would have been unable to exclude a problem at the stent edge.

The patient went back to the coronary care unit and made a good recovery from both his myocardial infarction and his chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation. He returned home a week later.

Scenario 2. How big is this vessel?

Angiography frequently underestimates the size of coronary arteries, leading to underexpanded stents, which are associated with subsequent worse outcomes. This is particularly the case in chronic total occlusions (CTOs).

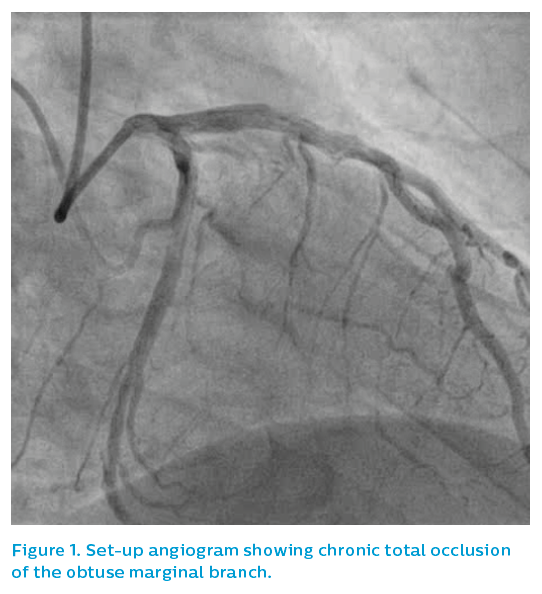

A 52-year-old male presented with stable angina and a positive stress cardiac MRI scan for ischaemia overlying the lateral wall of the left ventricle. Angiography showed a CTO of the obtuse marginal (OM) branch, see Figure 1, although the referring doctor expressed surprise that the vessel appeared to be quite limited in size for the extent of the perfusion defect identified and symptoms refractory to medical therapy.

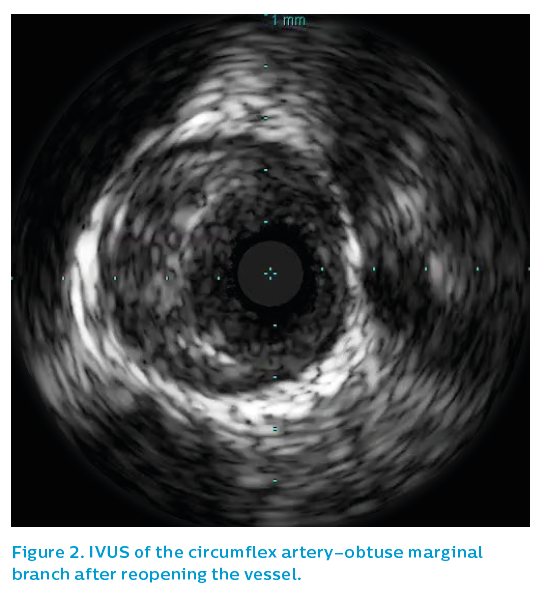

Once crossed with a Fielder XT wire and opened with a 2 mm compliant balloon, IVUS showed a much larger vessel than the angiogram had suggested, see Figure 2.

The IVUS oscillated in and out of the circumflex artery–OM bifurcation, showing atheroma extended back to the ostium, but the true ostium of the OM had a very short section free from disease, with marked disparity between the OM and the main circumflex artery.

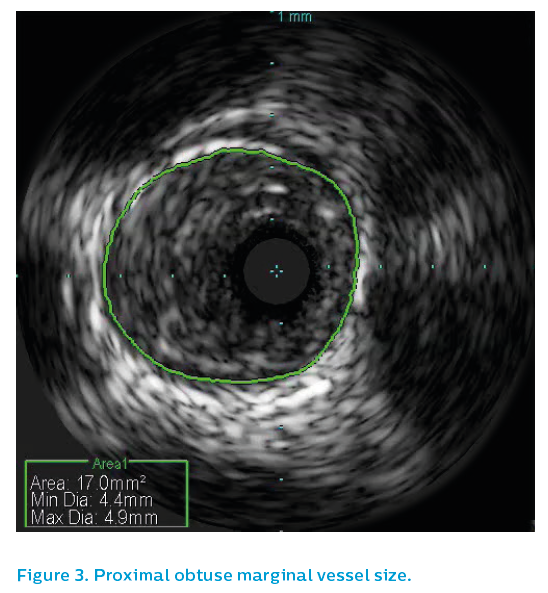

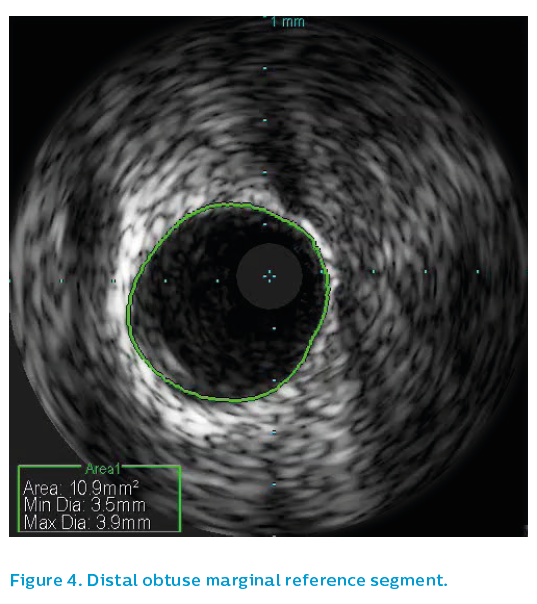

Surprisingly the proximal OM reference segment, see Figure 3, showed a 4.5 mm vessel, though this is partly due to positive remodeling. The OM distal reference segment, see Figure 4, showed a 3.5 mm vessel

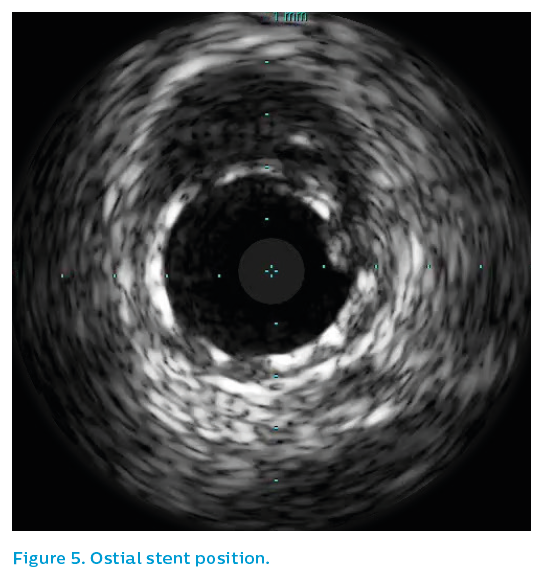

A 3.5 mm drug-eluting stent was sited from the ostium and post-dilated with a 4 mm non-compliant balloon to 26 atmospheres (atm), leaving a nice IVUS and angiographic result. Note that the OM stent hangs back into the bifurcation by a small amount. This was the only way to ensure ostial coverage. Figure 5 shows the bifurcation of the vessel with one strut back into the main vessel.

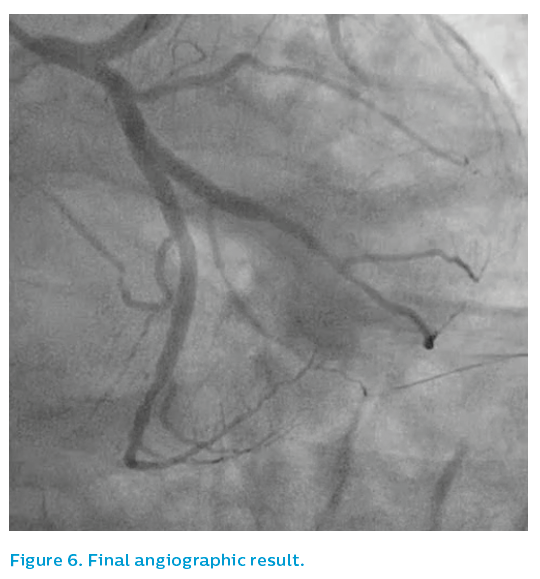

Note that the distal angiographic appearance of the vessel in Figure 6 gives the impression of a small vessel. IVUS shows no significant atheroma distally and, given the size of the proximal vessel, flow-mediated dilatation and remodelling of the open artery will likely show a bigger vessel at longer-term follow-up.

Scenario 3. 'A nice stent result'

An 81-year-old woman suffered a non-ST elevation myocardial infarction and underwent coronary angiography, which showed triple vessel disease, see Figures 1 and 2.

She was discussed at a multidisciplinary heart team meeting and, due to comorbidities, was turned down for surgery. She was accepted for percutaneous coronary intervention, which included rotablation of the left main stem and left anterior descending artery in the first instance.

The procedure was uneventful, with stenting performed from the left radial artery via a 7.5 Fr sheathless guiding catheter. The lesion was prepared with rotablation, see Figure 3, and then pre-dilated.

Stenting was performed from the mid-left anterior descending artery back to the ostium of the left main artery. Post-dilatation was performed using a 4 mm non-compliant balloon at 26 atm, producing a nice angiographic result, see Figure 4.

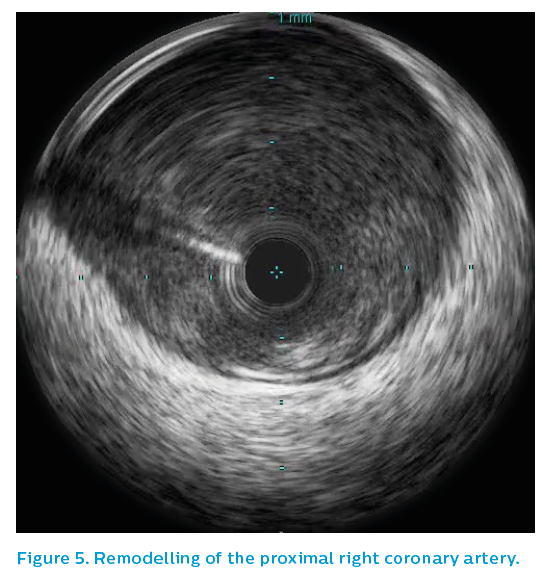

Following this, IVUS was performed, see Figure 5. The first greyscale run demonstrated significant malapposition at the ostium of the left main artery, see Figure 6, posing a risk of guiding catheter damage to the stent during this or future procedures. There would also be a risk of wiring behind a strut in any future percutaneous coronary intervention procedure that might be required.

The ostium was therefore post-dilated with a 4.5 mm non-compliant balloon and Chromaflo was used to check the result. Backing out the guiding catheter and oscillating in and out of the left main artery in a coaxial alignment revealed what could easily be missed on continuous run – continued mild malapposition, see Figure 7.

The vessel was further post-dilated to high pressure with a 5 mm non-compliant balloon. Figure 8 shows correction of the problem.

While eccentricity is not desirable, it is the final stent area that predicts stent failure. Therefore while high-pressure post-dilatation is usually recommended for all such stents, chasing stent eccentricity with repeated aggressive ballooning in the scenario of good minimal luminal area (>9 mm2 in the left main artery) is not recommended. Furthermore, malapposition with modern drug-eluting stents at the time of the initial procedure is not a strong predictor of stent failure. Rather, one is trying to avoid gross malapposition that might present a mechanical problem in future cases. One is also attempting to facilitate stent coverage with neointima, such that interruption of dual antiplatelet therapy will be less likely to present a clinical problem in the long term.

Persistent mild malapposition (<400 microns) is not a cause for concern if all reasonable attempts at correction have been performed. The final IVUS in Figure 8 and the final angiographic results, see Figures 9 and 10 appeared to be acceptable.

The patient returned at a later date for percutaneous coronary intervention to her sub-totally occluded and diffusely diseased right coronary artery, at which point angiography demonstrated a widely patent stented left main segment.

If we had left a grossly malapposed ostial left main stent, future intubations could have been hazardous. IVUS identified the problem and facilitated correction.

Scenario 4. Which lesion should be stented?

A 56-year-old male presented to a referring hospital with a troponin-positive acute coronary syndrome and inferior T wave abnormalities on his ECG. After initial medical treatment, he was transferred to a percutaneous coronary intervention centre for angiography.

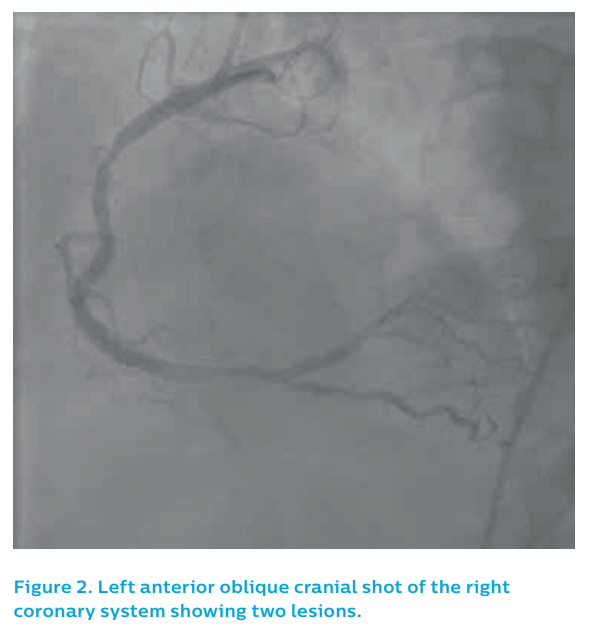

The left coronary system did not show a clear culprit, see Figure 1. The right coronary artery showed two potential causative lesions – one proximal and one distal, see Figure 2 – but it was unclear which of the lesions was the culprit.

The patient had been stable, with no chest pain, for the past 48 hours and had good coronary flow on angiography. The operator was concerned about the possibility of stent-induced embolisation from the thrombotic-looking distal stenosis and therefore elected to take the patient off the table and treat him with a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor. He was brought back for re-study 48 hours later, see Figure 3. At this time, the distal right coronary lesion appeared to have resolved, leaving only the proximal lesion.

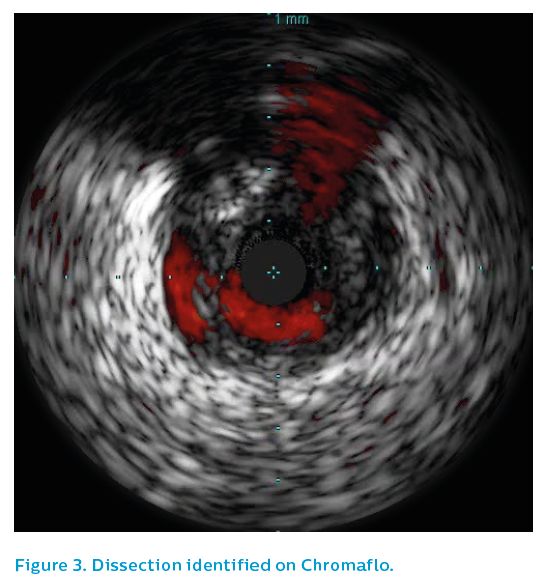

IVUS was performed using the Revolution® 45 MHz catheter. It showed residual eccentric thrombus adherent to non-ruptured mild plaque just prior to the bifurcation of the right coronary artery. See Figure 4.

coronary system showing two lesions

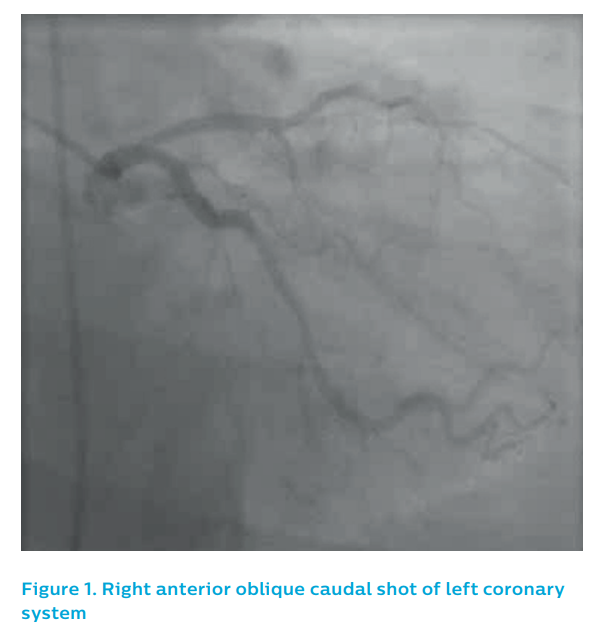

IVUS of the proximal right coronary artery showed intermittent positive remodelling, with extensive fibrofatty plaque burden, see Figures 5 and 6. A probable ruptured plaque was identified proximally. Presumably, embolisation of thrombus from this proximal lesion had occurred, landing in the distal bifurcation and failing to pass further due to the volume of thrombus embolised, see Figure 7. Only the proximal lesion was stented and optimised with post-dilatation.

The patient remained on potent oral antiplatelet medication for the following 12 months. The final angiographic result was acceptable, see Figure 8.

Scenario 5. What is happening at the edges of this stent?

A 56-year-old male was transferred to the catheterisation laboratory after repeated resuscitation from cardiac arrest. He was intubated and ventilated and on vasopressor support. His ECG showed intermittent inferior ST elevation.

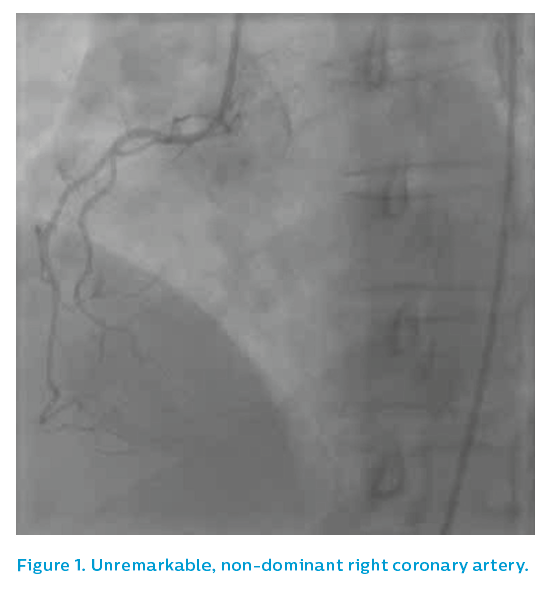

At angiography, the culprit lesion was unclear. The left system appeared to be unremarkable. The right coronary artery, showed a moderate proximal lesion, see Figure 1.

IVUS was performed, demonstrating a ruptured plaque in the proximal right coronary artery with overlying thrombus, see Figure 2. There was also 76% plaque burden at the site of an apparently moderate angiographic lesion.

Given his repeated inferior ST elevation and cardiac arrests, the patient underwent percutaneous coronary intervention. IVUS measurements showed a proximal reference segment of 4.5 mm and a distal reference segment of 4.2 mm. The operator was concerned about the possibility of thrombus embolisation. He therefore chose a cautious stent size, selecting a 3.5 mm drug-eluting stent, implanting at nominal pressure. This produced a ‘candy-wrapper’ appearance at either end, typical of either coronary spasm or dissection, see Figure 3.

As the appearances proved resistant to vasodilators, an IVUS catheter was passed to ensure that there was no dissection at either edge of the stent, see Figure 4. Despite marked angiographic abnormality, IVUS demonstrated that this was all spasm and not dissection, see Figure 5. There was minimal plaque present and a marked reduction in the vessel diameter compared to the pre-sent anatomy. The noradrenaline used to support blood pressure was exacerbating a tendency towards coronary spasm, and discontinuation of the drug assisted in recovery.

The eccentricity and underexpansion of the stent was treated with further post-dilatation and the final result was angiographically acceptable, see Figure 6. The patient did well with dual antiplatelet therapy. He was discharged home six days later with good left ventricular function and no residual neurological deficit.

Scenario 6. What caused this woman’s chest pain and ECG changes?

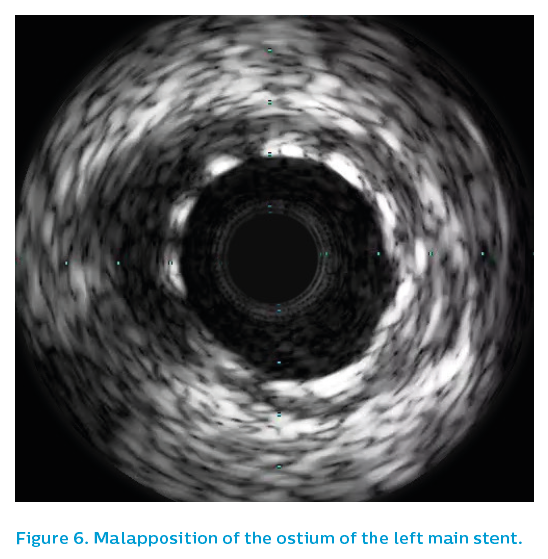

A 56-year-old woman suffered a significant emotional event and developed chest pain shortly afterwards. She came immediately to hospital. Her troponin levels were markedly elevated and she had anterior T wave changes on the 12-lead ECG. Early echocardiography was unremarkable and therefore she was listed for angiography.

The non-dominant right coronary artery was unremarkable, see Figure 1. The patient then underwent left ventricular angiography before an angiogram of the dominant left system was performed using a 5F JL3.5 diagnostic catheter, see Figure 2.

As the image quality was sub-optimal, see Figure 3, a guiding catheter was selected that demonstrated an irregular, spastic looking left anterior descending artery that did not respond well to intra-coronary nitrates. The IVUS Revolution® 45 MHz catheter was therefore used to assess the left anterior descending artery.

Surprisingly, the IVUS showed extensive spontaneous dissection, with intramural haematoma extending the apex (see Figure 4) to the proximal left anterior descending artery, see Figure 5. The dissection stopped in the proximal left anterior descending artery and IVUS demonstrated that the ostial left anterior descending artery and left main were not involved.

As with all spontaneous dissections, an attempt was made to manage the case conservatively. However, the left anterior descending artery became sub-totally occluded with recurrent symptoms. The patient therefore underwent stenting of the left anterior descending artery and was well at 6-month follow-up.

Scenario 7. Chronic total occlusion procedure?

A 72-year-old male presented with a troponin-positive acute coronary syndrome and inferior T wave changes. He came to the catheterisation laboratory for angiography, see Figure 1. The angiographic appearance of the right coronary artery was consistent with a chronic total occlusion. However, the presentation was consistent with acute coronary syndrome. Left coronary angiography showed moderate diffuse disease, which given the presentation and ECG changes, was felt to be bystander disease.

The lesion was relatively easily wired, raising the question of whether this was indeed the acute lesion. It was ballooned with a 2 mm compliant balloon to allow passage of the Eagle Eye® Platinum IVUS catheter. The greyscale and Chromaflo runs are shown in Figures 2 and 3. Note how the guiding catheter almost masked an ostial right coronary artery lesion. The operator realised that the true ostium had not been imaged and took the IVUS catheter back inside the vessel with the guiding catheter removed, showing a severe ostial lesion.

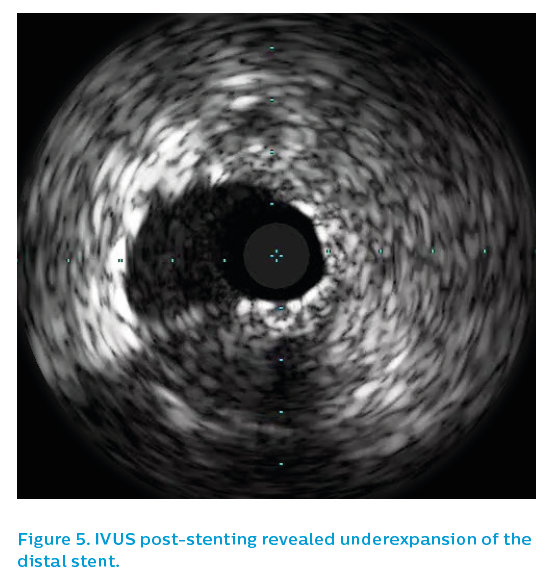

The first IVUS run demonstrated extensive fibro-calcific atheroma with a mid-vessel dissection, a proximal dissection and a small amount of thrombus. The presence of thrombus supported the concept of an acute-on-chronic lesion. The lesion was stented and, apart from a hazy, focal area in the proximal stent, the angiographic result looked reasonable, see Figure 4.

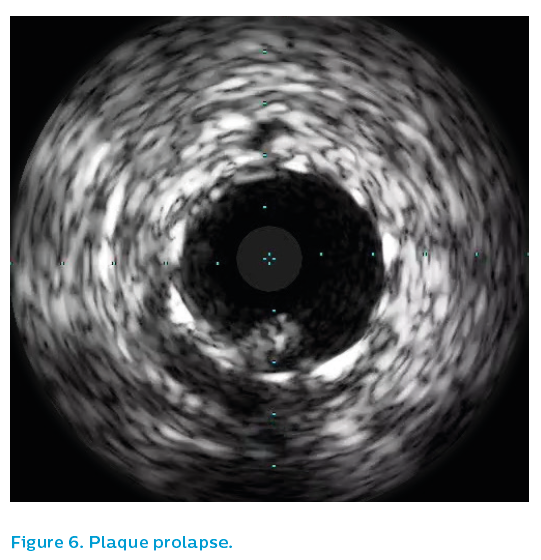

Further IVUS imaging showed a sub-optimally expanded stent and thrombus adherent to the wall, see Figure 5. The angiographic segment of interest in the proximal right coronary artery looked reasonable on IVUS, whereas the distal stent was markedly underexpanded in one plane with an exit dissection at the site of an eccentric calcified plaque. Plaque prolapse and thrombus, see Figures 6 and 7, were apparent at multiple sites along the stent, despite an activated clotting time of >250 seconds, emphasising that this was likely to be the acute lesion, despite the evidence of collateralisation on first angiographic projection.

High-pressure post-dilatation was performed with a 4 mm non-compliant balloon to 28 atm. A short stent was then deployed to cover the dissection at the outflow. The final optimal IVUS result is shown in Figure 8.

The operator stented back to the ostium, see Figure 9, given the IVUS finding of a severe ostial lesion. The guiding catheter was rocked back out of the vessel to ensure that the stent strut required in the aorta had not been damaged by the guiding catheter and that the true ostium had indeed been covered.

Multiple foci of thrombus were noted, but with a large vessel and TIMI 3 flow, the patient was treated with potent oral antiplatelet drugs without the need for glycoprotein IIb/IIIa treatment and did well.

Scenario 8. Very late stent thrombosis

A 76-year-old woman underwent stenting with a paclitaxel-eluting stent in 2006 for a non-ST elevation myocardial infarction. She did well for 10 years, until a protracted bout of diarrhoea and vomiting meant that she could not take her usual drugs, including her aspirin.

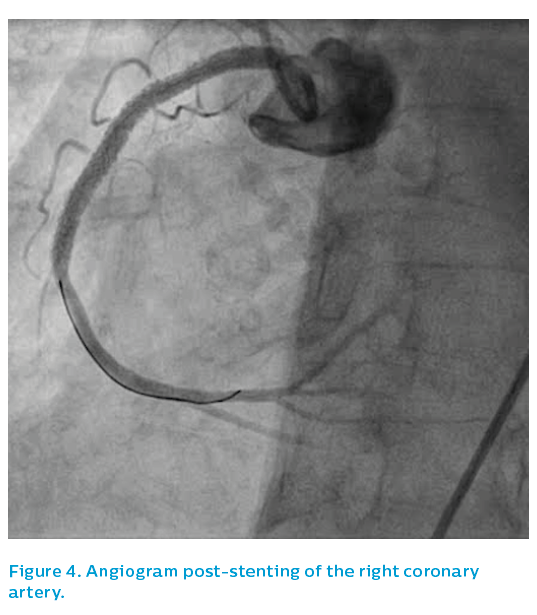

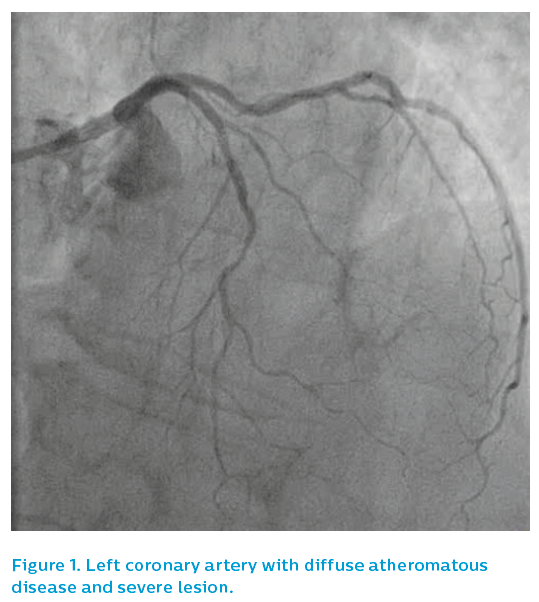

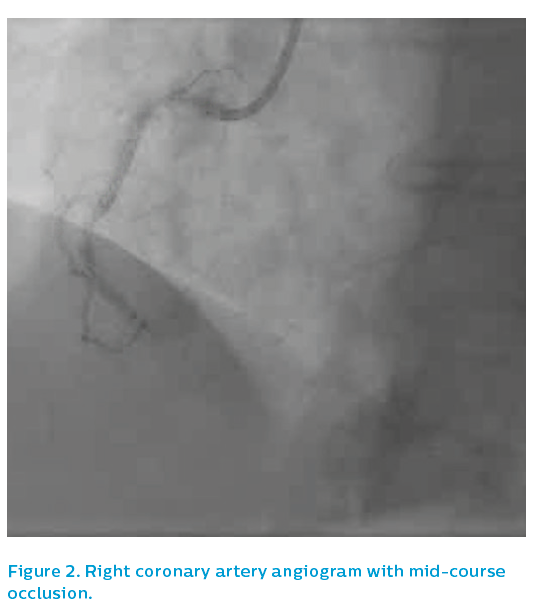

She presented after 3 days of D&V with inferior ST elevation myocardial infarction and was brought to the catheterisation laboratory. The left coronary system was patent, albeit with diffuse atheromatous disease and a severe lesion in mid-course, see Figure 1. The right coronary artery was occluded in mid-course, see Figure 2.

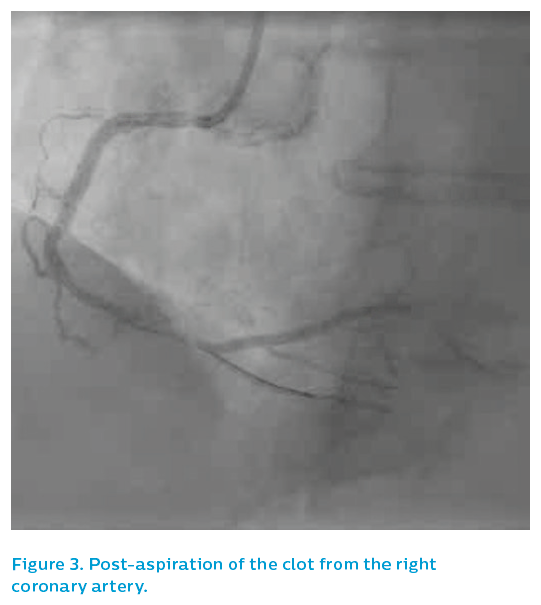

The patient was quite unwell at this point, with bradycardia and hypotension. An aspiration catheter successfully extracted a string of mature red thrombus, see Figure 3, restoring flow. The occlusion appeared to be within and adjacent to the old stent, angiographically. The patient was stabilised and, given that the mechanism of the infarction was in question, IVUS was performed.

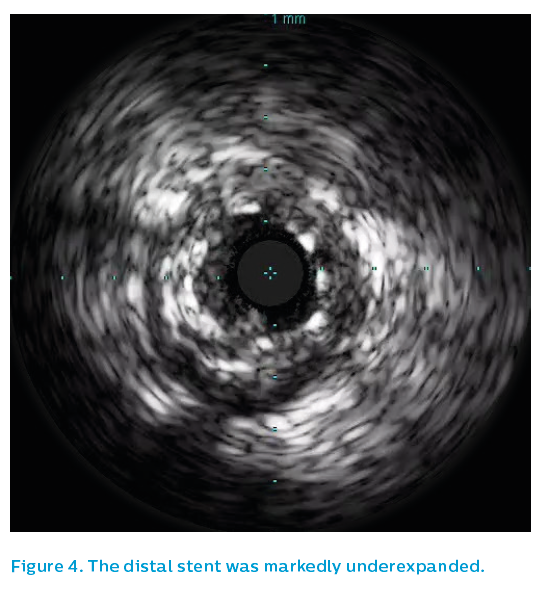

The IVUS showed thrombus and patchy neointimal coverage within a markedly underexpanded distal stent, see Figure 4. Proximally, the stent was underexpanded and had very little detectable neointimal coverage, see Figure 5. There was significant plaque burden distal to the old stent.

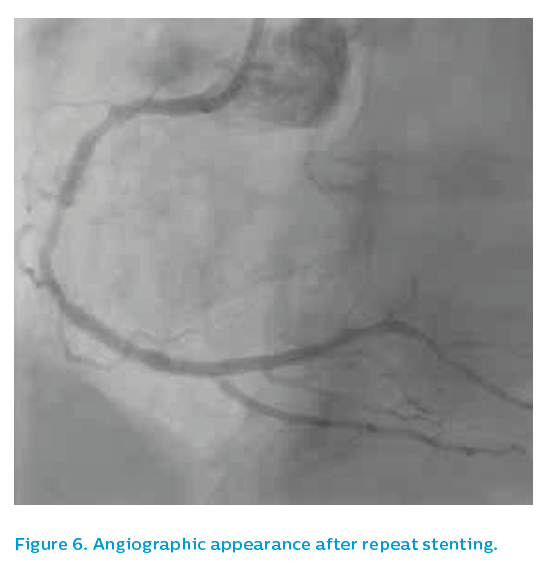

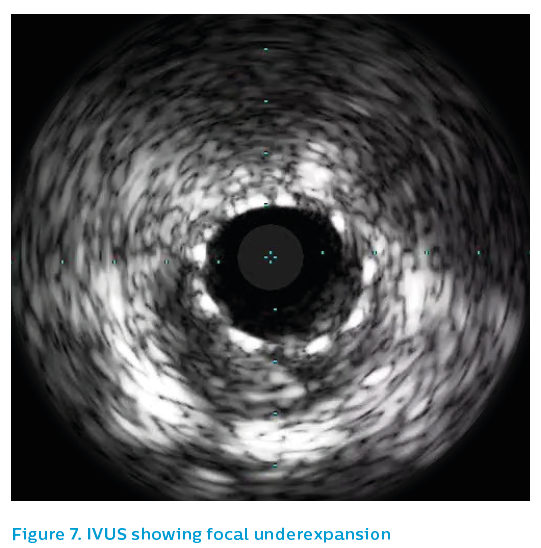

The old 2.5 mm stent was post-dilated with a 3.5 mm non-compliant balloon to 24 atm and then the affected segment was restented with a 3.5 mm Xience drug-eluting stent. Post-dilatation was performed using a 3.75 mm non-compliant high-pressure balloon to 24 atm. The angiographic appearance after repeat stenting is shown in Figure 6. The final IVUS run showed focal underexpansion of the stent at the point of the bifurcation (see Figure 7), and so a 3.5 mm non-compliant balloon was taken to 24 atm. This left a nice final angiographic result, see Figure 8.

The potential precipitants for myocardial infarction were multiple in this particular case. Aspirin malabsorption and the prothrombotic stimulus of diarrhoea and vomiting had exposed the underdeployed and uncovered paclitaxel-eluting stent struts to thrombotic stimulus in the scenario of outflow disease.

The patient was treated for a month with a potent oral antiplatelet combination, before being stepped down to aspirin with clopidogrel for the medium term.

She went home on day 3 and was free of symptoms at 12-month follow-up.

Conclusion

Angiography gives a guide to the lumen, just as exercise-treadmill testing gives a guide to the presence or absence of ischaemia.

Just as we are moving away from reliance on older noninvasive ischaemia-testing methodologies, which have clear limitations in terms of sensitivity and specificity, so we should be considering whether, in the catheterisation laboratory, the angiogram is always enough to accurately characterise the clinical problem.

Intracoronary imaging allows greater resolution of anatomy and is recommended for scenarios where the angiogram can be inconclusive or potentially misleading. Routine IVUS use shows that the angiogram is ambiguous far more often than we think.